Rob Eagar

An elderly woman who lives in my condo complex told me her mother had advised never to talk about religion or politics, a common caveat. The reason, of course, is that both are charged issues, and liable to arouse emotions that create discord, or worse, anger.

But there are times, I believe, when one should not remain silent. After all, if someone is offended by your honest concern for what, to any rational person, is a crisis threatening our form of government, do you want to keep quiet just to avoid hard feelings? Why should you care about what such a person thinks? Book marketing experts insist that authors avoid politics like the plague, but Rob Eagar has departed from that dictum.

“Do you know someone who thinks their political party or the president is more important than ‘the will of the people’?” he asks. “Boldly tell that person to knock it off. Or, urge them to move to China. They might feel more at home there. The collective voice of citizens who value democracy must overpower the extremist few who seek authoritarian control through intimidation and violence. As an American, your voice matters. You are ‘the will of the people.’ Democracy dies in silence.”

Tomb of Jesus

How refreshing. Religion, though, is a different matter. It’s completely subjective. Though it is easier to dissect the elements of political persuasion than those of religious conviction, both are usually influenced by the environment in which one was nurtured. If you grew up with parents of a particular political affiliation, there’s a good chance you will embrace that ideology as an adult. That is by no means true with everyone, however, as some think and act more independently than others. Religion, on the other hand, is more difficult to analyze by the use of reason. Thus, in my opinion, the big majority of believers subscribe to a particular faith because they were indoctrinated in it from birth, and never found a convincing reason to depart from it.

Federal prison execution chamber

Christianity is the predominant religion in the western world, the one I was reared in with strict adherence to its evangelical focus, i.e., the “ye must be born again” doctrine. But I always had problems with what I saw as huge contradictions in what I was taught. Not that I was steeped in the theology, but basic elements never have made sense to me, such as the idea expressed by a woman in my Facebook circle that “God loves all of us.” That doesn’t jibe with what happened to two guys in my upcoming book of creative nonfiction, both of whom led a miserable existence from day one and ended up beaten to death by prison guards or executed after almost 25 years on Death Row.

A highly intelligent classmate from the denominational college I attended many years ago located me recently, and sent a copy of the book The Case for Christ, which purportedly proves what we were taught to believe growing up and in the higher education we received. Authored by Lee Strobel, one-time legal editor of the Chicago Tribune, it presents exhaustive evidence of the resurrection of Jesus after his death by crucifixion. The book has sold more than five million copies, and a movie of it was made in 2017, receiving mostly favorable reviews.

Lee Strobel

Strobel was an atheist, and after his wife became a Christian, he set out to prove the story of Jesus’ resurrection was a fable, delving deep into the Bible to find historical discrepancies and contradictions. He researched intensively, and came up with 13 leading scholars and authorities to interview.

The story of Christ crucified, the body carried to a tomb, the tomb discovered empty two days later, and accounts of his disciples walking and talking with him days after his death is methodically picked apart by Strobel in the 13 interviews, and he finds the answers convincing. He then combines the evidence with a “leap of faith,” first postulated by Blaise Pascal, 17th century mathematician, physicist and religious philosopher, as a way of dealing with the resurrection as a miraculous defiance of the laws of nature.

Blaise Pascal

Strobel talks in the book about the miracles that the Bible has Jesus performing, as if these stories were credible, too. So, if you believe these events happened – for example, making enough bread from five loaves to feed 5,000 people, or raising Lazarus from the dead – then the next step into believing in Jesus’ own resurrection is entirely plausible. But I have difficulty believing these miracles. The means of communication 2,000 years ago were rudimentary, consisting mostly of word-of-mouth, and we know what happens to stories that are passed from person to person and generation to generation. It seemingly would be very hard to verify them.

A detail for which I’ve never come across an explanation is the deposit of Jesus’ body in a cave. If that were the entombment for everybody who died, they’d run out of caves, I should think. And Christ was not honored or celebrated by the authorities; on the contrary, he was so despised that they killed him. Why would the Roman authorities have guards posted at the entrance? Why would they care if somebody stole the body? In fact, if the body were left to rot, that cave no longer would be useful for anything.

The scholars whom Strobel interviewed were all evangelicals, that is, fundamentalists, despite their plethora of advanced degrees from such prestigious universities as Harvard and Yale and voluminous recondite publications. This causes me to suspect that they all were reared in Christian fundamentalism, which would lend a strong emotional bias to their scholarly pursuits, motivating them to prove what they grew up believing.

After Strobel was converted to Christianity, he became affiliated with fundamentalist Christian institutions, an appreciable number of which have been mired in scandal. He was a teaching pastor at Woodlands, a megachurch near Houston; at Saddleback, a megachurch in California affiliated with the Southern Baptist Convention; and Willow Creek Community Church near Chicago, which received national attention in 2018 for alleged sexual abuse by church leaders.

In early 2019, two large Texas newspapers found that there had been over 700 victims of sexual abuse from nearly 400 Southern Baptist church leaders, pastors and volunteers over the previous 20 years. Of late, the church organization has been embroiled in discord over its positions on LGBT rights, race, and politics. Churches in conflict with the SBC executive committee over these positions have been threatened with expulsion from the SBC.

David Fitzgerald

It bothers me that Strobel, a highly educated and reputedly astute seeker of truth, chose to be identified with religious institutions whose appeal is almost entirely emotional, its leaders relying on Hollywood-like methods of delivering Christianity’s message to mass audiences. Is it because such churches shield him from intellectual challenges to the faith?

Here are questions I would like to ask Strobel: 1) What happens in the hereafter to the souls who lived before Christ, and never had a chance to accept Jesus as their savior? 2) What happens to the Christian message if some form of human life is discovered on another planet or planets?

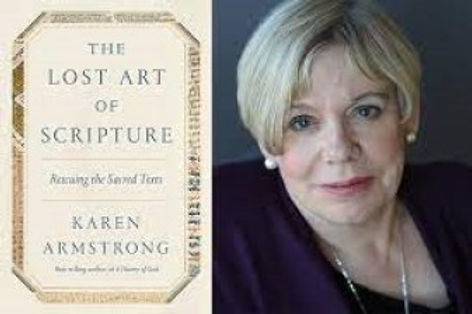

I have not read the critiques of Strobel’s book by such opponents as the religion scholar Karen Armstrong, and only cursorily checked on atheist David Fitzgerald’s appraisal (tinyurl.com/8smsw464, containing damning revelations), but what I read has contributed to my suspicions about the book’s authenticity.

I rest my case.