George Saunders

In middle and high school literature classes, I remember grousing about having to look for the “hidden meanings” in short stories, mainly because I could never find them. Why don’t the authors just tell us what point they’re making, I wanted to know, without forcing us to bust our brains trying to figure out the riddle – much as Poe’s character in The Purloined Letter “hid” a blackmail letter in an open card holder that police ignored, instead searching the apartment’s nooks and crannies?

In later years, I wrote my own short stories, without being clever enough to inject any hidden meanings – except possibly for one, titled Progress. It’s in a compilation called The Way We Were: Short Stories and Tall Tales, available as an ebook on Amazon ($.99). It has a man visiting the site of a home where he lived decades before as a child, his nostalgia interrupted by armed robbers holding up a bank now occupying the property. As he and family members drive away in the aftermath, he marvels at how neatly landscaped and gleamingly modern the once-rustic area had become.

Edgar Allan Poe

The message, I explained to a close relative who read it, is that appearances can be deceiving, and what looks lovely can hide evil lurking. She suggested I spell that out.

No no no, I objected. That’s like telling a joke and then explaining its meaning. The comic effect would be ruined. It’s funny because you are puzzled at first (depending on how astute you are), and then it hits you. In a short story, the dramatic impact is neutralized.

Those hidden meanings in short stories are what George Saunders explores in the book A Swim In A Pond In The Rain. Saunders, an acclaimed short story writer himself, won the prestigious Man Booker Prize for Fiction with his first novel, Lincoln In the Bardo, which has created a buzz in recent years. In this year’s A Swim, he presents several of his favorite short stories by revered Russian authors, and analyzes them.

President George W. Bush

The book was loaned to me by a most interesting friend who never voted until becoming appalled at what President George W. Bush was doing to the country. Yet the mustachioed Ed is highly literate and well-informed. To celebrate his 65th birthday, he swam a mile in the ocean (not in the rain) – and repeated the feat five years later. He’s an expert ballroom dancer, an avid fan of horse racing, and a habitual reader.

It took me a while to get through the book, but I learned a lot, including the understanding that the lessons short story authors mean to convey are not always fathomable. They can be cryptic, and have the potential for more than one interpretation. Saunders himself wasn’t certain, for example, of what Leo Tolstoy meant to tell us in Alyosha The Pot, from 1905.

Leo Tolstoy

Alyosha is a homely young man, a hard worker who is abused psychologically by his employers, his father, and children who gave him the Pot label after he dropped a pot of milk during an errand, breaking it. (The yarn reminded me of the time, in graduate school at the University of Iowa, I allowed my attention to be diverted by a comely lass while carrying a three-gallon pot of hot soup to the serving area in the school cafeteria, and the pot slipped out of the hand towels I used to grip the hot rim. Soup everywhere, and a lady worker’s toe was singed.)

Yet he cheerfully performs his tasks with utmost obedience. Everyone takes advantage of him except for a young woman named Lustinya, whom he falls in love with and proposes marriage to. His father mercilessly condemns the idea, calling her a “town slut.” Instead of defending her, Alyosha says they’ll have to obey his father, and doesn’t comfort her when she cries. What appeared to be a positive characteristic is now shown to be weakness. But when his boss’s wife later admonishes him to forget the marriage idea, he cries, showing he has feelings, understanding his father’s unfairness and suffering guilt over failure to defend Ustinya from him.

So what will happen next? Might Alyosha become bitter, causing him to rebel and get fired, or perhaps take to drinking? Saunders entertains several possibilities, then says, “Tolstoy does something smart: he knocks Alyosha off that roof.” He’d resumed his passive ways, but was cleaning snow from a roof and fell off, dying from his injuries and smiling as he departed three days later. It’s a surprise ending, and “has the effect of forcing all of the psychic consequences of the broken engagement to play out within a compressed time frame.”

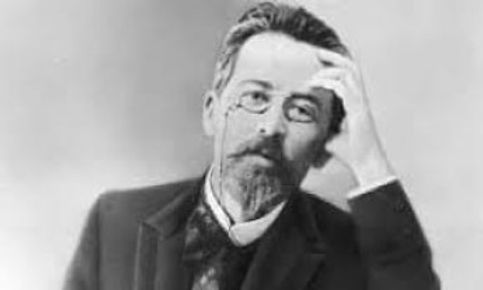

Anton Chekhov

We readers want to know what Alyosha is feeling as he dies. Saunders offers us various options, but leaves us to decide which Tolstoy meant. It is this mystery that is so compelling. Because we know the author intended to convey something important.

The short story requires greater attention than the novel, in which peripheral events and details of interest, but not of critical significance to the storyline, can be introduced. On the other hand, Saunders says, “the story form makes a de facto case for efficiency. Its limited length suggests that all of its parts must be there for a purpose. We assume that everything, down to the level of punctuation, is intended by the writer.”

Saunders makes this point in discussing his favorite of the book’s seven stories, Gooseberries, by Anton Chekhov. It has two hunting buddies taking shelter at the country home of a younger friend, where one, Ivan Ivanych, embarks on a story about his brother, a low-level bureaucrat who yearns to own a piece of land, and finally attains happiness in that accomplishment. That is the foundation for a troubling question that Chekhov raises: the nature of happiness.

Ivan Turgenev

Nikolai Gogol

“Behind the door of every contented, happy man,” Ivanych says in his impassioned story, “there ought to be someone standing with a little hammer and continually reminding him with a knock that there are unhappy people, that however happy he may be, life will sooner or later show him its claws, and trouble will come to him.”

Such ideas cannot be lightly dismissed. They stimulate contemplation, packing a wallop with their laconism. And so it goes with all of the other marvelous stories in this collection, which Saunders adroitly vets: In the Cart and The Darling, by Chekhov; The Singers, by Ivan Turgenev; The Nose, by Nikolai Gogol; and Master and Man, by Tolstoy.